Following Palm Sunday I went into retreat for Holy Week, first on the remote Shetland Isle of Fetlar and then on the ‘most northerly’ monastery back on Unst. Below is a little a taste of this time, which lay at the heart of my Wild Monastery pilgrimage. Unlike during the rest of my travels, my retreat included stepping back from online journalling and I wrote no facebook posts during this time. So the photos and reflections written here afterwards are the only record.

Although Fetlar is not the furthest flung of the Shetland Isles, in some ways ways it feels more remote than its more northerly neighbour, Unst. The ferries to and from Fetlar are much less frequent and the population is much smaller. People and their places feel in a minority compared to ‘more than human’ world there, such that it felt like a real wilderness space to me. I was talking recently to one of my sons about this and of his experience of growing up in a retreat centre in a wilderness location on the West Coast of mainland Scotland. We were reflecting together on how living in such a place permanently alters one’s sense of self and life. It is a visceral experience of being a small part of a much greater whole, within which one has limited power and control in the face of the elements, the landscape and its wild creatures. Living in a city, town or even sometimes in the well farmed rural south, this is often not apparent and there can be a loss of connection, not only with our being a part of nature but of with a humility about actually being a small part of the complex eco systems on which we all depend. Living in the wild was the foundation for me of founding River Dart Wild Church and Wild Monastery, as a way of life that recognises the reality of this interdependence.

So life on Feltlar for those fews days felt wild… and very windy! Within this I felt very blessed to be staying at a lovely retreat centre in the warm and welcoming home of Ruth and Graham Booth. Graham met Mother Mary Agnes, founder of the monastery on Unst that would be my final destination later in the week, some years ago on a retreat of his own. At that time the religious order she began, The Society of Our Lady of the Isles (SOLI), was based in a house on Fetlar. It sounds like Graham’s pilgrimage there was a significant step towards him and Ruth later moving to Fetlar themselves, where they have converted what was the Church of Scotland Manse (where the minister would have lived, so like a vicarage further south). Its location at Tresta is particularly spectacular as it sits at the edge of a narrow curve of land that lies between a big, beautiful sandy beach and a wide expanse of fresh water called Papil Water (from Papa, meaning priest). The Kirk is just a short walk from the Manse and is a true wild church in this naturally sacred space of sea and sky. Ruth and Graham have been actively involved in a local community group who have managed to buy this kirk, during the recent years of re-structuring in the Church of Scotland, which has seen many smaller, rural churches being sold off. This means it will remain a consecrated place of prayer and open to anyone who feels the call of the sacred wild. What a blessing!

Graham and Ruth are ‘new monastics’ like myself, which made for a happy meeting! They are members of the Community of Aidan and Hilda, which was founded by Ray Simpson on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, where Graham was previously Warden. Like most new monastics they have created their own daily rhythm of life around four times of prayer in their peaceful attic chapel. I so appreciated my three days joining them in this, with the sense of companionship that quickly grew in gathering together regularly around the table – both at the chapel altar and the in the dining room. While there, I chose to stay close to home and enjoyed wandering and wondering in their garden, which is very special for Shetland in having a small, sacred grove of mature trees. I also found a little, sheltered, stone walled corner for silent prayer in the graveyard (as shown above) and made walking meditations, while being blown along by the ever present wind, at the sea’s edge. A particularly pleasure was ‘grazing’ on the flowering purple brassicas in the polycrub, a more robust Shetland equivalent of a polytunnel. The relentless reality of Shetland winds makes the shelter and ensuing warmth within a polycrub feel like such a sanctuary. If I ever live in Shetland, I will be wanting to create a polycrub chapel!

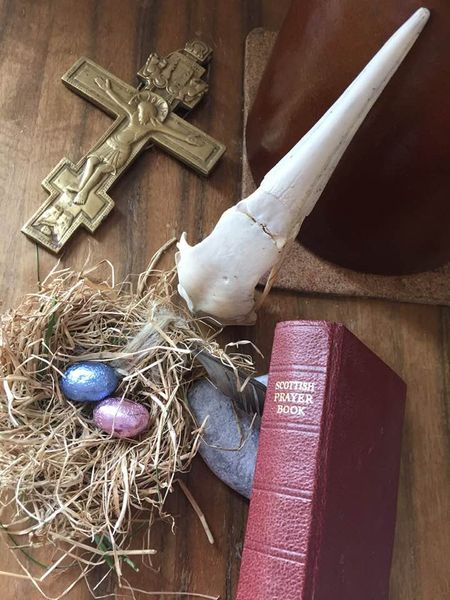

After this prayerful and companionable time, by the morning of Maundy Thursday it was time to shift gear, move into silence and make my way back to Unst to stay alone in Britain’s most northerly monastery. The last of the nuns who were based there moved out in the autumn of 2022, so I was very grateful to have been given permission by the SOLI Trustees to stay there. The purpose of my retreat was not only to approach the Mysteries of the Paschal Triduum, in those three days between the evenings of Maundy Thursday and Easter Sunday, but also to discern whether the Holy One may be calling me a new monastic hermit life on Unst?

I don’t want to write much about those days. I remember when I was teaching our Wild Wisdom School course and how, when we looked at the ancient Mysteries of Eleusis, we were all struck by the wordless power in their ceremonies, at the heart of which a priest would simply and silently hold up an ear of grain. This invitation to contemplation is so resonant with wild symbolism, of growth and harvest, generosity and transformation. As Christ says in the Gospel of John: ‘Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.’ (Chapter 12, verse 24). What I will say here and now, is that I felt very unwell from late on Maundy Thursday through Holy Saturday. All the embodied memories of my months suffering with covid and my struggles in the Church of England seemed to rise up and I found it hard to breathe. I rarely feel lonely, for all that I spend much time alone, and yet in those days I felt the remoteness and exposure of the monastery, and the harshness of the far northern weather and landscape. Perhaps it was the weaving together of my story and the Christian story of the crucifixion and descent into hell/Sheol/death, in those days of silent and solitary contemplation held within the potentised prayer space of chapel there.

Then I woke on Easter Sunday feeling completely different, as if I had been set free! The sky was a vast and heavenly blue, people at the Easter Sunday service in the local Kirk were kind, and the slow sunset over the great expanse of shining sea was breathtaking in an entirely inspiring way. Yet I felt grateful for the preceding days: the opportunity to dive deeply into my fears and painful memories and to be sobered by acknowledging some of the more challenging realities of staying in this particular environment. Having co-created and lived in a retreat on the last croft, in the last village within a remote community on the West Coast, I am no stranger to some of the issues involved and one of the many things that place and its people taught me was to open my heart to the whole of life, to look for blessing in both beauty and struggle. Shetland is that bit further north with its longer winters, darker nights, windier days and further flung for all that needs to travel there, be it people, supplies or services, and that needs to be taken seriously. So I felt tempered and strengthened in my sense of the Holy One’s call to the hermit life and simply open to whatever might unfold in the days, weeks and years to come…

All text and images are my own – © Sam Wernham 2023